Photo: Kelly Hebestreit

By Jack Palen

Should every adult in the United States vote? America’s answer to that question is and has historically been “hell, no.” The earliest American elections were restricted to land-owning white men, making voter suppression one of America’s longest-standing traditions.

News flash: seven of the 17 Amendments to the U.S. Constitution address increasing accessibility to the polls. How sad is it that the document guiding this country had to be edited seven times to let folks vote – and still it does not do enough. The 13th, 14th and 15th amendments really did not even enfranchise Black men fully, and if you believe that the 19th Amendment enfranchised all women in this country, then Native American, Asian, and Black women would like a word.

To this day, the Constitution does not explicitly give every American adult the right to vote and some state laws bar large swathes of the public from the polls. Legal residents cannot vote. Those with felony charges cannot vote. Our incarcerated population cannot vote. Those without permanent addresses cannot vote. These demographics represent millions of people who live in a democracy with which they cannot engage.

But voter suppression is not just sweeping, codified law prohibiting folks from voting, it also encompasses superfluous procedures, legal or illegal, that distance voters from the ballot box. The act of voting is not necessarily difficult, it is deliberately made that way by those in office. If the U.S. values democracy as much as it boasts, voting would be the most convenient thing in the world. Sadly, voter suppression is as American as apple pie. It is a story that is far from over: at least one of the two major American political parties relies on the suppression of votes to win elections.

Millions of Americans have their vote suppressed each election cycle, perhaps without even realizing it. You are probably one of them.

Voter Suppression is a Tool of White Supremacy

Following the Civil War, more than half a million Black men became voters, and governments in the South reacted, as healthy democracies do, to these changes to the electorate. In Mississippi, two Black U.S. senators were sent to Washington and in 1868, South Carolina’s legislature was majority Black. Before non-white voters were enfranchised, the South had never seen this. When the Reconstruction-era federal occupation ended in 1877, white supremacists became more confident and active in suppressing non-white votes. Once white Southerners retook control of state legislatures, the laws once again began to change.

New federal Constitutional amendments prevented white southerners from barring non-white voters outright, so they instead chose to make it much more difficult for non-white people. On top of extralegal violence from groups like the KKK, states implemented poll taxes requiring payment from voters before casting a ballot, which newly emancipated citizens could not afford. Arbitrary literacy tests were also implemented widely. In Mississippi, non-white voters were made to read sections of the state constitution to the clerk before entering, and often also had to explain its meaning. The voter’s worthiness of casting a ballot was left up to the white clerk.

Further, southern states codified “grandfather clauses” that barred from the polls anyone whose grandfathers were not able to vote before the Civil War, effectively blocking all but white voters. In Mississippi, post-war voter suppression brought Black male voter participation rates from above 90% to under 6%, rates similar to other southern states. These practices continued through the Jim Crow era in conjunction with increased political intimidation and violence.

Vote for Those Who Can’t

The Voting Rights Act of 1965 (VRA) sought to protect the rights guaranteed by the 14th and 15th Amendments, ending racial disenfranchisement and holding states accountable for their historic discrimination. The passage of the law brought a huge increase in non-white voter registration, and jurisdictions had to pass a federal “test” before they could pass voter and electoral laws. The Supreme Court struck down parts of the VRA in 2013 and diluted the federal government’s power to provide election oversight. Not only did the decision halt some progress of the VRA, it opened the door for states to continue legally suppressing voters.

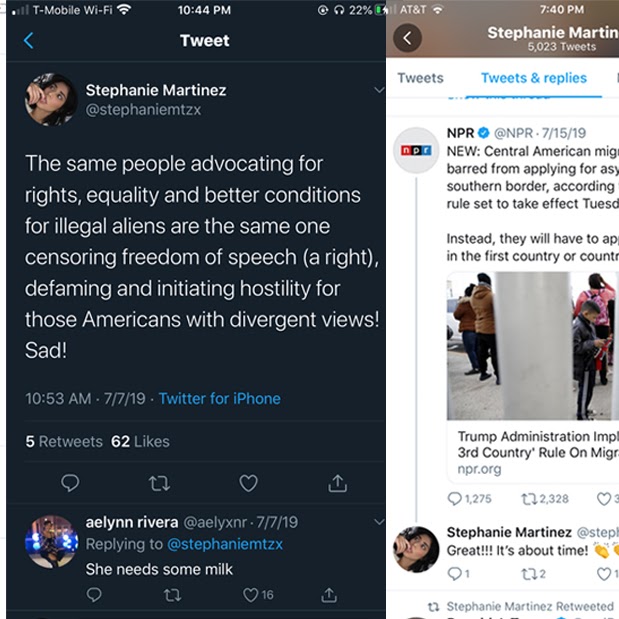

Convoluted voting information, voter ID laws, voter roll purges, inaccessible polling sites, and absentee hurdles are the modern tools that those in power use to ensure you and other Americans cannot vote them out of office. These are only distractions, extra hurdles to jump through without justification. Most suppressed demographics lean left, namely people of color, which might explain the (mostly) Republican tendency to sabotage elections.

Many would agree that Stacey Abrams, the first Black female gubernatorial candidate for a major political party in U.S. history, would-be governor of Georgia if Brian Kemp, then secretary of state, had not removed several hundred thousand voters from the registration list and blocked 50,000 others from registering. Atlanta-based civil rights advocate Joe Beasely, called it what it was, saying, “Kemp has abused his power to purge the voter rolls […] of Black and brown people.” When Georgians recently attempted to vote in the 2020 primaries, many were met with faulty voting machines and long lines. State officials simply blamed poll clerks, because it’s easier to blame logistical failures rather than admit to dismantling a democratic state.

In 2018, voting rights advocate Theryn Bond rode Memphis public transportation from her home to her polling site to show the Tennessee election commission how burdensome voting can be for individuals when polling sites are not properly placed. Bond’s round-trip took six hours. Transportation needs and time commitments can determine whether an individual can vote, and it's a more difficult decision for low-income voters, who may need a ride or time off work. Why do Republicans target low-income voters in this way? Consider for a moment that Donald Trump lost to Hillary Clinton in every subsection of voters making under $50,000 per year.

For many, election day requires months of planning and preparation. For Louisiana residents, it is essential to register and request absentee ballots a full month before election day. This is difficult for those who may not have the bandwidth to constantly be worrying about being prepared to vote. And when you think it can’t get worse, know that Louisiana has made Congressional and Presidential general elections fall on two separate days, with their own registration guidelines. Why?

Republicans are getting so good at suppressing votes that they should get paid to do it. Wait—they do. Voter suppression is not only a part of the job, but it is also an essential Republican strategy. Rep. Glenn Grothman (R-WI) said in 2016, "Clinton is about the weakest candidate the Democrats have ever put up [...] we have photo ID [laws], and I think photo ID is going to make a little bit of a difference..." Great job, Rep. Grothman! No shit. Justin Clark, a senior advisor to Trump’s reelection campaign, said last December, “traditionally it’s always been Republicans suppressing votes in places [...] that’s what you’re going to see in 2020. It’s going to be a much bigger program, a much more aggressive program, a much better-funded program.” Folks, this is terrifying.

If you are a young student voting in an election in a red state, there is a solid chance that your elected officials do not want you to be able to vote. Suppression like this inhibits state and federal governments from properly reflecting the will of the electorate. This should scare us. After all, if you do not see yourself in the government, how invested can one expect you to be?

Wait—Is my Vote Being Suppressed?

Surprise! It is likely that you face unnecessary barriers to voting. To answer this better, let’s look at some key questions we can ask ourselves to see who modern voter suppression might affect and what it looks like.

Is Election Day confusing or convoluted?

Let's be clear, if a state government wanted to make voting easy, it could and would. Recall the Louisiana example, where presidential and congressional elections are on two separate days. This effectively doubles the amount of labor a voter must take on in order to vote. Holding federal elections on one day and making that day a holiday could make voting simpler. What does your state do?

Are multilingual voter registration forms available?

If you live in the U.S., your state’s secretary of state is the person in charge of elections. Is their site clear and available in several languages? What about registration forms? In 2008, the Iowa Supreme Court allowed the then-secretary of state to only produce English language registration forms. As a result, eligible voters in Iowa who did not speak English could not easily register and did not vote. When information is confusing, only online, or only in English, potential voters might be unable to meet the requirements to vote.

Does your state have a Voter ID law in place?

Most likely. A total of 36 states have some sort of law in place which requires state-sanctioned identification in order for an individual to vote. Voter ID laws are, in many ways, the reincarnation of poll taxes, since most forms of state-sanctioned IDs cost money to obtain. Voting should be completely free, but many still have to spend money to vote. How does your state handle identification? Will you be affected? How much money does one need to spend in order to be able to use their voice in this country?

Are polling sites accessible and efficient?

Studies by the Election Administration and Voting Survey and the U.S. Census Bureau show that counties with large minority populations are hit hardest by ill-placed and under-staffed polling sites. In 2018, urban centers of large metropolitan areas had especially few poll workers per active voter and faced shutdowns of polling sites at rates greater than more affluent areas.

Even if one makes it to a polling site, outdated machines and overworked clerks frequently result in long waits. If individuals have other obligations, the opportunity cost of voting becomes too great. Is your state election system receiving the funding required to be efficient, accessible, and convenient?

What does registering and voting look like in your state?

If your state’s registration deadlines vastly precede election day, your state is suppressing potential votes. In Alaska, for example, you have to be registered and ready to vote a full month before election day. In Vermont, alternatively, you are able to register and vote on election day itself. When states make election day a multi-day, multi-faceted ordeal, it puts an undue burden on those who do not have the privilege and energy to keep up with information and preparation. When states allow for individuals to register and vote at polling places on election day, it ensures that the door to voting is open for those who might have fallen behind in preparation.

After the 2018 elections, Arizona changed its laws to require a sworn affidavit and a legal ID in order to vote after election day, even if the state is still counting absentee ballots. Without Googling it, I literally could not even tell you where one would obtain a sworn affidavit. Why would a government do this?

Can young people vote easily?

For years, Austin Community College in Austin, Texas, has used its own funds to host early-voting sites on nine of its eleven campuses, and in 2018 those sites logged 14,000 votes. Last year, the Republican-led state legislature prohibited the event, outlawing polling sites that do not stay open for the entire early-voting period. Students lean blue, which might explain why Republican states cringe at the fact that students are turning out in record numbers. In 2018, 40.3% of all American students voted more than double the rate of the 2014 midterms, a trend that is likely to continue.

Many states do not incentivize voting for college students. In Tennessee an individual can use a firearm registration card to vote, but not an in-state University ID. Out-of-state students may also have to have their absentee ballots stamped by a notary. I can’t even tell you where my closest notary is.

Does your state purge voter rolls?

This is no joke. Roll purges swing elections and affect people directly. Many states literally take registered people off of the registration list, forcing individuals to register again if they skip an election. Not only does this require additional labor to vote, it especially affects those who are unable to easily vote or register. Imagine missing one election and having to redo the already laborious process. After Brian Kemp purged scores of voters from the Georgia roll in 2017, many voters were caught off guard. James Baiye II, a Georgia resident, was excited to vote for Ms. Abrams in the state gubernatorial race, but when he got to the polls he was turned away. He can thank Brian Kemp for that.

Are my state’s districts oddly shaped?

Check out what your state’s congressional districts look like on a map: are they oddly shaped, dipping through cities and rural areas in seemingly arbitrary ways? These districts may have been shaped this way to manipulate the voice of the electorate. This is called gerrymandering, a tactic used to sway congressional races so states send redder or bluer delegations to the U.S. Congress. Your state may do this.

Can my neighbors with disabilities vote easily?

Probably not. For many of the 35 million voting-age Americans with disabilities, voting is an ordeal. According to a 2018 report by the Government Accountability Office, almost two-thirds of the 137 inspected polling places had at least one impediment to people with disabilities on election day in 2016. Polling sites must follow ADA regulations like any other establishment. Does your state take it seriously?

This is Bullshit. What Can I do?

Say “screw you, I am voting anyway,” and make sure no obstacles keep you from the polls. Included in this document is a spreadsheet of relevant dates and deadlines for each state. Check out which dates you need to be aware of, and always check state websites for information too. If you are planning to vote in-person, plan ahead to prepare for travel time, getting out of work, or taking care of obligations so you have time to go to the polls. Reach out to friends, plan carpools, make it a party.

Our generation has had enough. Once we are registered and ready to go, let’s not vote for people who will work to suppress our friends and family. If you do not agree with your state’s approach to elections, let your elected officials know. Your secretary of state is likely the one who leads your state’s elections. Reach out to them to demand accountability and reform, and let these electoral issues inform your vote.

Emma Goldman once said, “If voting changed anything, they'd make it illegal.” She’s right, and for many in the United States, voting is and has been illegal. Voting is essential to our republic, and vigilance is required to protect that right. Today, incarcerated people are systematically disenfranchised, and even after the completion of their sentences, many lose their voting rights for life. Many Americans without permanent addresses, including over half a million Americans experiencing homelessness, cannot vote. Is this truly right?

The election system must work for everyone and we must understand how access, or lack thereof, is strangling our republic. This November, take initiative, register, and vote, if not for yourself, then for those who cannot.

Other Resources

Post a Comment